The ice flood and its solution

The ice flood and its solution

The war on ice (part 2)

In June 2013, as part of Drug Action Week in the ACT, I delivered a paper called How many cones? How many pills? How many lines of coke? estimating the size of Australia’s illicit drug.

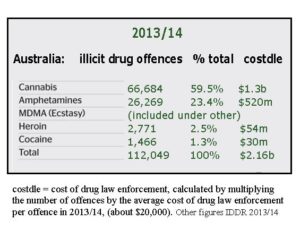

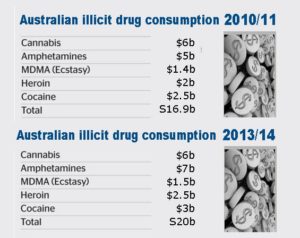

My paper estimated that the Australian illicit drug trade in 2010 consisted of a market of about three million Australians. It was worth about $17 billion; composed of a cannabis market, worth about $6 billion, a heroin market of $2 billion, a cocaine market of $2.5 billion, 40 million ecstasy tablets worth about $1.4 billion, and 6.8 tonnes of methamphetamine, worth about $5 billion. The cost of drug law enforcement I estimated at $1.5 billion.

When I recently updated these estimates using the most current data from 2013/2014, the other drugs markets were relatively stable, but the war on ice caused the cost of drug law enforcement to rise to $2.17 billion, the total illicit drug market rose to $20 billion, and the amphetamine market increased to nine tonnes with a street value of $7 billion. The more money we spent to suppress the Meth monster, the more it grew.

For the police, the prominence of the war on ice allows drug prohibition to be sold as a crusade against folk devils, the outlaw motorcycle gangs, but the reality of drug prohibition is a war on cannabis. Sixty per cent of drug arrests were for cannabis in 2013/14; it was seventy per cent of arrests in 2010/11, but the doubling of the arrests for amphetamine offences over the next three years, caused the percentage of cannabis to go down , even though the number of cannabis offences went up by eight thousand.

Queensland keeps winning the war on drugs in Australia. It has the most number of drug arrests, as well as most cannabis arrests. Queensland came first in steroid arrests, and over 60% of the nation-wide arrests for steroids were from Queensland; it also came first in hallucinogen arrests as well as other and unknown drugs arrests.

There were 66,684 cannabis offences in total in the financial year 2013/14: Queensland led the way with 20,219 cannabis offences; New South Wales was second with 15,756; Victoria third with 8,588 offences, followed by Western Australia recording 8,286 offences.

Queensland police target cannabis users, blindly following directives laid down by Premier Bjelke-Petersen forty years ago, who declared that he wanted to drive all the pot smokers out of Queensland.

Victoria led the arrests for amphetamine-type stimulants with 7555 offences, closely followed by Queensland with 6772 offences, with New South Wales not far behind.

Even though cocaine is similar to ice in its physical actions and it’s potential for abuse, cocaine arrests were only 1.3% of all drug arrests. Cocaine is almost decriminalised in Australia because it is the drug of choice for the highest socio-economic class, who are four times more likely to be cocaine users than the population in general. Methamphetamine users are as numerous as cocaine users but tend to belong to the lower socio-economic groupings and they make up 23.5% of drug arrests. Although cannabis is a far safer drug, a cannabis user is ten times more likely to be arrested than a cocaine user. (Cannabis is almost equally popular with all classes.) When the police drug-test drivers, they don’t test for cocaine and benzodiazepines, deliberately turning these function off so they will arrest neither the rich nor housewives.

For reasons of class rather than considerations of harm-minimisation, the police are waging a war against cannabis and the amphetamines, not cocaine. The police conduct their version of the war on drugs and they are concerned, not with health outcomes, but with arresting those suspected of belonging to the criminal classes and protecting the property of the wealthy. In practice, this translates into the extraordinary low prosecution rates of cocaine offences.

The total number of drug offences was 112,049, another record. More drug offences were prosecuted in Australia than ever before, a phenomenal quantity of drugs was seized, and the size of the illicit drug market has never been bigger.

Insanity, said Einstein, is repeating the same action and expecting different results. Since we are still trying to arrest our way out of the problem, our drugs policy is clearly insane.

Sensible drugs policy

The war against ice is proving to be one of the most futile and costly social experiments ever undertaken in Australia. Billions of dollars have been spent prosecuting the war, hundred-thousands of drug offences have been prosecuted, tonnes of ice have been seized, and yet the country is awash with methamphetamines.

In 2014, former Victorian police commissioner and head of the National Ice Taskforce Ken Lay admitted “we can’t arrest our way out of this problem”. But arresting people is all the police know, so they blindly continue. Their attempt to arrest their way out of the ice problem has been counter-productive, provoking the flood. The war on ice has been an enormous failure. The police are the wrong weapon to use because their approach only keeps prices high when the aim of policy should be to lower price, so the global methamphetamine cartels will lose interest in Australia.

Australia needs to adopt a policy of harm-minimisation, which may mean we have to choose the lesser of two evils: and the lesser of the two evils we face, methamphetamine and MDMA, is MDMA.

The arrest-your-way-out-of-the problem approach has led to the ice flood in other ways besides globalising supply. It was the police suppression of the MDMA market in 2009 that created the space for the ice epidemic to grow.

In the decade between 2000 and 2009, Australia experienced an MDMA flood, and this flood caused very few problems. In 2008 the UN declared Australia had the highest MDMA usage in the world; and in 2007 Australia set a world record for the biggest ever MDMA seizure, the only seizure to rival the monster of November 2014. It was huge; over four tonne! Yet most people are unaware of the MDMA flood because it caused negligible social problems, in contrast to the ice flood.

To respond to the ice flood, we need to use drug policy, rather than the police. The first action should be to decriminalise cannabis and MDMA. We can then move carefully to regulate MDMA though pharmacies, who have been preparing to dispense medical cannabis. Because it is a chemical, MDMA would be appropriately dispensed by pharmacies, but cannabis, which is a herb, not a chemical, might be better served by other distribution mechanisms. The regulation of MDMA would provide a legal and safe alternative to ice, and lessen demand, and lessen price. It would be a far more effective strategy to deal with the ice flood. Although not providing direct competition, the decriminalisation of cannabis would serve to lessen the profits of the black market.