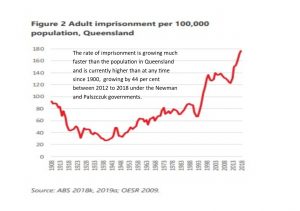

Queensland’s prisons are in crisis. Prisons are overflowing and are operating at 130% of capacity. The state outlays $1 billion dollars annually on prisons, and is faced with building another two new prisons to house an anticipated four thousand extra prisoners over the next five years. The expenditure needed for these prisons alone is estimated to be $3.6 billion dollars.

In 2018 the Labor government asked the Queensland Productivity Commission to investigate Qld’s burgeoning prison population; in particular, the high imprisonment rate of people in Queensland, which was around five times the population growth rate, the high rate of recidivism with more than 60 per cent of new prisoners having been in prison before, and the high imprisonment rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. A team of researchers examined scores of submissions from stakeholders and the public, interviewing many at public hearings. They produced a 700 page report, the Queensland Productivity Commission report on Imprisonment and Recidivism, which was finally released to the public in February 2020, six months after the commission gave the report to the government, who held it back, apparently terrified by its level-headed recommendations.

For the QPC dared to suggest the Queensland government needed to question whether the current reliance on incarceration as the solution to many health and social problems was working. They wrote:

“Incarceration has profound impacts on prisoners, their families and the community— loss of employment, housing, relationships, as well as mental health problems—all of which increase the risk of reoffending. In this report, we ask whether community safety is best served by continuing the current approach.

“Is there a case for some crimes to be punished with non-custodial options? Could better outcomes be achieved with greater attention to rehabilitation and reintegration? Would some offences be better treated as medical issues rather than criminal offences? Should victims be empowered by building in restitution and restoration options? Early indications are that the community may actually be made safer by reforming current practices.”

(2)

Keith Hamburger was appointed Queensland’s first Director General of Corrective Services in December 1988 and he remained in this position until June 1997, when he left to head the Public Service Board. Since then he has remained a passionate advocate of prison reform and restorative justice. As the prison world is closed off from the general population, I asked him to give an overview of the make-up of Queensland’s prison population and how prison services were coping with the growing number of prisoners.

“The prison population of Queensland is composed of 31% of First Nations people. These make up only 4.6% of the population so they are grossly over-represented. Typically, about 40% of prisoners are functionally illiterate. We have a lot of people with substance abuse problems; about 15% of prisoners suffer some degree of mental impairment and these days we have a lot of people with mental health problems, driven by a lot of factors that are driving criminality, so prison today is a repository for a lot of people with severe mental trauma. These are the people we are dealing with.

“Another thing about the prison population is a significant proportion are there for a relatively short period of time. According to the QPC report, 52.9% of prisoners are discharged within 6 months. Our prisons are so over-crowded that they can’t provide rehabilitation services for anyone who is in for less than 12 months, so most of our prisoners are not getting any rehabilitation at all; they’re being put into jail, then tipped out on the street without any rehabilitation, and we wonder why we have such high levels of recidivism? It’s a no-brainer!

“Another terrible thing is that most of these prisoners who make up over 50% of the prison population are housed in high security prison cells that cost $$600,000-$800,000 to build because we have nowhere else to house them. An absolute waste of money!”

One of the QPC report’s solution to the rising numbers of prisoners is to reduce the rate of imprisonment through less reliance on imprisonment as a punishment for a number of non-violent crimes that do not have a victim: this category included drug possession offences, motor vehicle and some driving offences, regulatory offences and public nuisance offences; these minor offences make up about 30% of the prison population so a non-prison option like community service programs would lower prison numbers significantly and help avoid the $3.6 billion needed for new prisons.

The recommendation for the legalisation or decriminalisation of cannabis is sensible and is ‘courageous’ only by Queensland standards: Canada legalised cannabis in 2018: eleven US states have legalised cannabis and several others are due to vote on cannabis legalisation in 2020. In Australia, the ACT legalised cannabis this year and New Zealand will vote to do so at the end of the year. The legalisation of cannabis will happen eventually, (because we slavishly follow the US) and pushing it forward will take considerable pressure off the prisons and police and avoid the trauma of drug-police home-invasions.

The QPC subjected its suggestion that Queensland should decriminalise or legalise cannabis and MDMA (Ecstasy) to a cost-benefit analysis. It estimates Queensland is currently spending $500 million annually on drug law enforcement and that the decriminalisation of cannabis and MDMA would be a net benefit of $850 million dollars annually to the Queensland economy, while the benefit of the legalisation of cannabis and MDMA would be higher around $1.2 billion.

Most of this saving would be provided by cannabis law reform and there is majority community support for changes to the cannabis laws. Nonetheless, decriminalising or legalising MDMA should be considered as a practical solution to the methamphetamine flood the country has been experiencing over the past decade.

Legalising or decriminalising MDMA would give Ecstasy an economic advantage over ice. Both drugs are stimulants, but Australian history shows that MDMA creates far fewer social problems than ice. The first decade of the twenty-first century saw Australia awash with MDMA, with few resulting social problems, but the global MDMA shortage of 2009 laid the basis for the great Australian methamphetamine flood that dominated the next decade, which caused significant social harm.

The War on Ice kicked off around 2010 and it has proven to be an enormous social policy disaster, which has greatly magnified the methamphetamine crisis. The 44% rise in the rate of imprisonment in Queensland between 2012 and 2018 has been significantly fuelled by the War on Ice: Queensland went from 3,320 amphetamine arrests in 2010-11 to 11,511 arrests in 2017-18, an increase of 250%. Queensland is spending $500 million annually on the War on Drugs and about $200 million of that amount is spent in arresting, prosecuting and imprisoning amphetamine providers and users.

By cracking down on meth, the police forced the price up. Because Australia had the highest price in the world for methamphetamines, the major global criminal meth-producers targeted the Australian market, flooding the country with ice. The War on Ice, caused Australia to be awash with ice. The Australian record seizure for methamphetamine rose from 240 kilos in 2011 to 1.6 tonnes in 2019, while the world record for methamphetamine seizures of 1.7 tonnes of meth was intercepted in California on its way to Australia in the same year. These massive seizures, hyped by the media and the police, celebrated by politicians gloating how well ‘tough-on-drugs’ was working, had no effect. After a decade of sensational ‘Ice Kills’ government advertising and vigorous police suppression, methamphetamine is now Australia’s biggest illicit drug trade, worth $9 billion annually, jobs, jobs, jobs for importers, wholesalers, street-dealers, the vast army of meth pushers.

Unfortunately, the QPC report seems like another excellent report that will never be acted on, judging by the way the Palaszczuk government reacted; they hid the report for six months, and released it into the COVID-19 storm. They rejected any softening of the drug laws in a one-line sentence that says tersely that ‘the Queensland Government has no intention of altering any drug laws in Queensland’. Instead of action, they propose to appoint another committee to report on the report; they seem to be kicking the can further and further down the road, hoping the troublesome report will quietly expire.

To be continued: Discussion on crime and punishment in Queensland is dominated by the Murdoch press and the radio shock-jocks, who fuel fears of crime and deviance, and offer simplistic solutions like ‘lock ‘em up’, and three-word slogans like ‘law and order’, and being ‘tough on drugs’ and ‘tough on crime’ to promote a punishment paradigm for the treatment of crime and deviance. The political class have crumbled cravenly to these amplified inanities, which explains the terror of the Palaszczuk government at appearing ‘soft on drugs’. ‘Tough on crime’ has become the consensus paradigm across the political divide: so each year more people are arrested, resulting in a steadily rising prison population that continues to be housed in expensive high security jails. In the ensuing articles, I will examine an alternative paradigm, restorative justice.